Many students and residents agree: Murfreesboro, Tennessee, has a sidewalk problem. Throughout the city, pedestrians can be seen traveling on the side of the road, through grass, in ditches and along dirt paths.

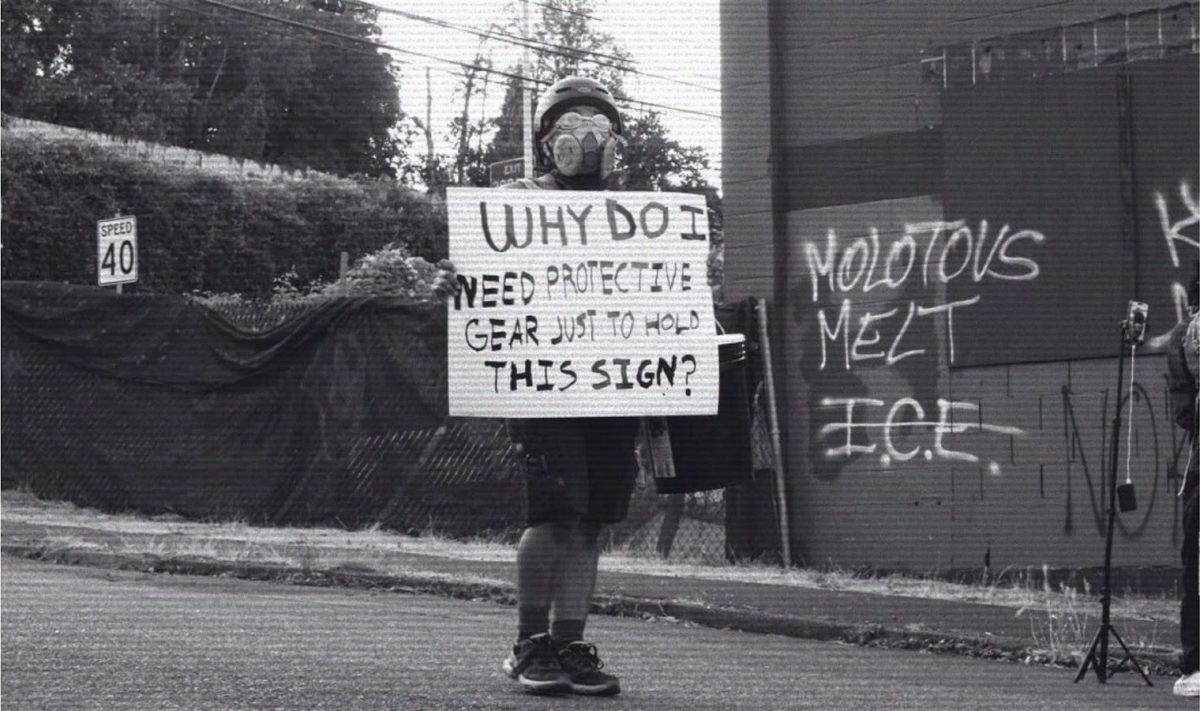

Traveling down Old Fort Parkway, one of Murfreesboro’s busiest areas, it isn’t difficult to spot a variety of pedestrians – people in suits carrying briefcases, houseless people pushing shopping carts, hotel guests or teenagers – trying to navigate the busy highway. They tread through tall grass and dodge vehicles as they attempt to cross the street.

Despite this, the area is rated “Above Average” for walkability, according to the National Walkability Index.

“This is not normal,” Jesennya Furtado, an MTSU student and Massachusetts native, said. “Y’all have all this landscape and roads, but no sidewalks. It’s been a lot of times when I had to walk, and it was really unsafe for me to, especially when there are people going 40 miles per hour and up. I can literally feel the cars passing.”

Many residents share Furtado’s sentiment. However, statistics paint a different picture. According to the National Walkability Index, Murfreesboro ranks “Above Average” in walkability. Some of the city’s densely populated areas, such as Northwest Broad Street, East Main Street and the MTSU Campus, receive a “Most Walkable” rating compared to surrounding areas.

These pockets of walkability are exceptions, though, not the rule, said Keith Gamble, an economics professor at MTSU. While some areas comprise much of Murfreesboro’s “walkable” territory, they only represent a small portion of the city.

“Murfreesboro’s walkability is limited,” Gamble said. “There are several places in the city where you can’t walk safely from place to place. There are neighborhoods with no sidewalks; you have to walk on the street. The city is not built for easy walking … there’s the expectation that everyone drives from place to place.”

What makes a city walkable?

The EPA’s National Walkability Index, released in 2021, outlines the criteria used to assess an area’s walkability, including intersection density, proximity to transit stops, diversity of employment types (such as retail, office, service) and diversity of housing types.

While the Walkability Index measures the likelihood of residents traveling on foot, it does not include criteria for assessing the presence of sidewalks, crosswalks, or trails in these areas.

“I think more sidewalks are definitely the best solution,” said Jaela Smith, a resident and MTSU student. “Murfreesboro’s [roads] are actually very connected to each other, and just by having more sidewalks, I feel like we could probably lessen traffic … especially around campus, like it’s sidewalks all around there, but only to a certain point.”

Sidewalks only extend so far around the MTSU campus, forcing off-campus students to find alternative routes to get to classes.

“There’s some, but they’re not great,” said Alyssa Hildebrandt, an MTSU international student. “And I find that they’re very sporadic and not consistent. Like the sidewalk will randomly end in some places.”

This lack of consistent sidewalks leads residents such as Hildebrandt to feel unsafe.

“I don’t really think [Murfreesboro] is a safe place to walk because there’s not many sidewalks. So, I think the chance of getting hit by a car is really high,” Hildebrandt said.

Smith shares Hildebrandt’s sentiment. Despite living five minutes from campus, she avoids walking.

“I’ve been a Murfreesboro resident for three years. I stay right around the corner from campus…and I can’t walk without possibly getting hit by a car,” Smith said.

Walkability scores often overlook pedestrian safety when evaluating walkability, resulting in a skewed perception of accessibility in these areas.

Murfreesboro and the broader Metro-Nashville area have been linked to some of the nation’s highest rates of pedestrian accidents. In recent months, several pedestrian crashes have occurred in Murfreesboro. In December, a woman was fatally struck near The Avenue Mall on Medical Center Parkway. In March, a man was left in critical condition after being hit on South Church Street. Most recently, in April, a pedestrian was struck while crossing John Bragg Highway.

Gamble believes walkability scores overlook many key factors, especially in growing cities that want to attract more people.

“Walkability, I think, is very difficult to do. There are a lot of different factors, and some of those factors are hard to get data for everywhere,” Gamble said. “Any city’s going to have more walkability than rural areas, but that’s not really relevant to people’s experience.”

And when measuring walkability, distance matters, Gamble said.

Murfreesboro is a pretty spread-out city, and the interstate, of course, is definitely a huge barrier to walkability,” he said.

Public transit also plays a critical role. While the EPA’s criteria include proximity to transit stops, it doesn’t consider the availability or reliability of that transit.

“I don’t trust public transit because it’s unreliable,” Hildebrandt said. “So, I won’t take it unless I have to, and calling an Uber or anything like that is unreliable as well. There was one time I was going to take an Uber to an appointment, and the Uber was an hour late.”

Some residents agree that walkability requires more than adding sidewalks and public transit. Statistically, pedestrian accidents are more common in densely populated areas. As Murfreesboro continues to grow, so must its leaders’ approaches to safety, emphasizing the shared responsibility of drivers and pedestrians to ensure everyone’s safety, said Gamble.

“Drivers certainly need to keep their eyes open … and be more patient,” Gamble said. “Everyone seems to be in a big hurry to get where they’re going … and walkers sometimes have to be extra careful. Even if the crosswalk light’s on, some cars just assume because it looks clear, they can still go.”

To improve transportation, city officials announced that the new Murfreesboro Transit Center opened in April. The $17 million project expanded bus routes and operating times, offering citizens more efficient service. The center also serves as a central hub for buses, making transfers easier and public transit more accessible for residents.

“I think it’s a good start, and we’ll just have to see how it goes,” Gamble said. “But, just like any city, there’s always more we can do.”

This story was originally published on MTSU Sidelines on October 16, 2025.