Column: My old friend Jennifer

‘Recovery isn’t a straightforward path, it’s bumpy with potholes and boulders.’

Alexa Hernandez

“I wouldn’t say Jennifer’s gone, she’ll never truly be gone, she’ll always be a small part of me.”

May 11, 2023

The sound of my mom crying, the uncomfortableness of the hospital gown, the different faces coming in and out trying to figure out what was wrong with me.

It’s something I know all too well.

I knew I looked different from other kids. I would stretch out my clothes so they would fit, the fabric feeling like it was crushing my lungs, my family even gave me the nickname ‘chubby cheeks.’ I didn’t let it affect me, I didn’t care enough. I loved food, it always worked as a substance of serotonin. Yet, as I got older, the comments started rolling in.

“I think Taylor needs to lose weight.”

I was 9.

“I just think Taylor eats too much.”

I was 10.

“Don’t tuck your shirt in like that, it makes your stomach look big.”

I was 11.

I became more aware of my body, I wanted to change how I looked. I wanted to be prettier, I wanted to be skinnier.

I was 12.

During the start of COVID-19, I was always at home. It gave me a lot of time to look at my 12-year-old body. I started noticing the little things.

Little things I needed to change.

I started to starve myself, I skipped countless meals and soon only let myself have a small portion of dinner per day.

I would check my body in the mirror multiple times a day to see if I had gotten any skinnier with each meal I skipped.

I would sneak into my parents room and steal their scale to weigh myself each time I thought I hadn’t lost any weight.

I would over-exercise in the boiling summer heat, running around my backyard desperate for a flat stomach. My little body almost passed out every single time, just to try and lose weight my body desperately needed to get rid of.

I deemed ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods, I didn’t let myself have the ‘bad’ foods. ‘Good’ foods were low in calories and ‘bad’ foods were high. I would only allow myself to have the ‘good’ foods. Those that were tasteless, water based and small in portion.

I never gave my body enough food, I was always fatigued. I checked my body at least 10 times a day at that point, constantly nitpicking tiniest of things about myself I didn’t like. My mental health was at a steep decline. My anxiety worsened, and soon enough I developed depression. I hurt my body in more ways than one, yet I felt so powerful. After months of repeated unhealthy behaviors, my body finally started to look like what I saw online.

Skinny.

Pretty.

Acceptable.

No one noticed anything wrong with me. No one noticed the full plates of food I threw away, my skin vacuum sealed around my bones, my wrists now smaller than a child’s, nothing.

Life was normal until my checkup with my pediatrician. I had seen her a month earlier, but she saw something peculiar about my labs, so I was told to come back. This was the appointment. I had my weight, height, blood pressure and heart rate taken. She looked at my results on her clipboard, taking a deep breath before saying the eight words that made my whole life fall apart.

“You need to take Taylor to the hospital.”

My eyes widened as I tried to process those words, I didn’t understand.

I lost 20 pounds in under a month.

My mom, dad and I rushed to Children’s Medical Center in Plano. But due to COVID-19, my dad had to stay in the hospital lobby for the entire four hours I was there, scared out of his mind. My mom stayed in the room with me, anxious she was going to lose her youngest child to this unknown sickened killer inside of me.

Nurses came in and out of my room, each face came in with a different task: to draw pints of blood, to question me, to question my mom about what I was experiencing. All just to figure out what was wrong with me. I received the news.

I was diagnosed with an eating disorder: anorexia.

I was 12.

Nurses threw treatment options at my mom and I, yet we had no idea what to do. I didn’t believe I had a problem, I didn’t see anything wrong with me. I just wanted to look like the other kids. I was trying to help myself and my parents have a normal child. Not an overweight, ugly, worthless one.

I was forced to start treatment in August 2020, a month after the hospital fiasco, but due to COVID-19, it was online through a Zoom call. I began with a partial hospitalization program (PHP) at Center For Discovery (CFD), an eating disorder specialization center. At CFD, myself, and other clients were in treatment from 12-6 p.m. having lunch, a snack and dinner. I would have breakfast and two snacks, not on the call. Three meals, three snacks. So much more than I was having before, I was overwhelmed.

CFD has many therapists and dieticians for support on the journey to recovery. I met with a therapist twice a week, and a dietician once a week to discuss a meal plan I would follow to help gain weight. I went in-person to CFD’s office every Tuesday to get my weight and blood pressure taken for logs, so they could mark my progress and make tweaks to my meal plan if needed.

I was so agonized I had to go to PHP, and even be in treatment, I genuinely didn’t think there was anything wrong with me. I was in so much denial about my ED, I just wanted to be skinny, to have my dream body.

PHP wasn’t helping. Because it was on a Zoom call, it was easy to hide my food so I wouldn’t have to eat it. I wasn’t honest, I told the staff I was eating it but I wasn’t, I couldn’t. I had a demon inside of me I couldn’t control.

I did PHP for a month, and my therapist and dietician recommended I go to residential treatment. At residential, you stay at a house with other people with EDs and are monitored 24/7. It’s the highest level of care before they send you back to a hospital. With residential, there was no way I would be able to lie to anyone anymore about what I was really doing.

My mom did not want me to go to the residential, she didn’t want to be at home all by herself, for her youngest to be at a house with a bunch of strangers. At this point, I partially realized I had a problem, I wasn’t confident in it, but I wanted my old life back, I needed to go. It took long, dreadful conversations, but I finally convinced her to let me go.

I turned 13 right before I went to the residential.

I had to explain my story to new people. The new clients, the new therapist, the new dietician, everyone. I hated sharing my story, I felt ashamed.

It took weeks of residential for me to finally get adjusted to recovery. The early mornings, the meal and snack schedules, the Saturday blood draws, the dreaded scale, being away from my family. A month of real residential recovery allowed me to realize I had a problem.

I was determined to change.

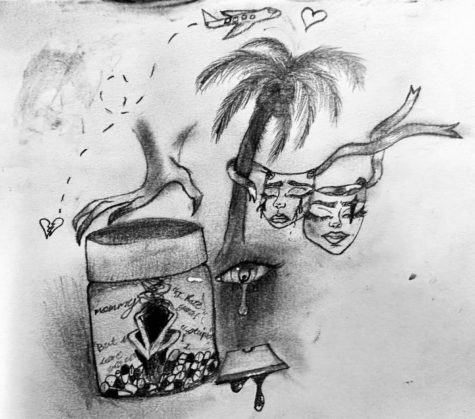

I started to make so much progress at residential after I realized there was something inside of me that wasn’t me. It was my ED, Jennifer. My therapist at residential came up with Jennifer as a name for my ED, I stuck with it. I made new friends who I felt like I could talk to without feeling judged. I learned dozens of new coping mechanisms to deal with my anxiety and depression instead of looking for it in my ED.

I went to the residence in early September and left late November. Residential was a rollercoaster of emotions, but I learned so much about myself and about who Jennifer was.

Jennifer didn’t care about me. She only cared about what my body looked like. She made me believe I had to be skinny to be pretty. But I was a child, I was still going through changes, I wasn’t developed yet.

I wasn’t even close to being done with treatment, so I went back to PHP, but this time, in person. I was monitored whenever I ate, so I could hold myself accountable to finish my food. I brought my own dinner, they provided snacks and lunch. I made even more friends there, and even saw some of the people who I went to residential with.

I was in PHP for four months where I continued to make unbelievable progress and soon made it to the lowest phase of treatment, intensive outpatient program (IOP). I only had to go to treatment three days a week, and I only had to be there for three hours instead of six. IOP lasted for two months.

On Feb. 26, 2021, I graduated from CFD. It’s the biggest accomplishment of my life.

I was 13.

Today, I am still in therapy, I still see a dietician, but I have my old life back. I’m out of the treatment that sucked up my whole first year of being a teenager. Now, I see my friends, I see my family, I’m coping healthily, and I’m so much happier. Treatment taught me how to accept myself, my body and learn that Jennifer isn’t me. Jennifer wanted to kill me, if I kept listening and believing her, I wouldn’t be alive.

I wouldn’t say Jennifer’s gone, she’ll never truly be gone, she’ll always be a small part of me. Every once in a while, she’ll show up, but I’ve learned how to ignore her. Recovery is not a straightforward path, it’s bumpy with potholes and boulders ready to take you down. Recovery is possible, and so worth it.

I am 15.

This story was originally published on Farmers’ Harvest on May 5, 2023.

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-1200x676.jpg)

![Junior Mia Milicevic practices her forehand at tennis practice with the WJ girls tennis team. “Sometimes I don’t like [tennis] because you’re alone but most of the time, I do like it for that reason because it really is just you out there. I do experience being part of a team at WJ but in tournaments and when I’m playing outside of school, I like that rush when I win a point because I did it all by myself, Milicevic said. (Courtesy Mia Milicevic)](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/c54807e1-6ab6-4b0b-9c65-bfa256bc7587.jpg)

![The Jaguar student section sits down while the girls basketball team plays in the Great Eight game at the Denver Coliseum against Valor Christian High School Feb. 29. Many students who participated in the boys basketball student section prior to the girls basketball game left before half-time. I think it [the student section] plays a huge role because we actually had a decent crowd at a ranch game. I think that was the only time we had like a student section. And the energy was just awesome, varsity pointing and shooting guard Brooke Harding ‘25 said. I dont expect much from them [the Golden Boys] at all. But the fact that they left at the Elite Eight game when they were already there is honestly mind blowing to me.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_7517-e1716250578550-900x1200.jpeg)

![BACKGROUND IN THE BUSINESS: Dressed by junior designer Kaitlyn Gerrie, senior Chamila Muñoz took to the “Dreamland” runway this past weekend. While it was her first time participating in the McCallum fashion show, Muñoz isn’t new to the modeling world.

I modeled here and there when I was a lot younger, maybe five or six [years old] for some jewelry brands and small businesses, but not much in recent years,” Muñoz said.

Muñoz had hoped to participate in last year’s show but couldn’t due to scheduling conflicts. For her senior year, though, she couldn’t let the opportunity pass her by.

“It’s [modeling] something I haven’t done in a while so I was excited to step out of my comfort zone in a way,” Muñoz said. “I always love trying new things and being able to show off designs of my schoolmates is such an honor.”

The preparation process for the show was hectic, leaving the final reveal of Gerrie’s design until days before the show, but the moment Muñoz tried on the outfit, all the stress for both designer and model melted away.

“I didn’t get to try on my outfit until the day before, but the look on Kaitlyn’s face when she saw what she had worked so hard to make actually on a model was just so special,” Muñoz said. “I know it meant so much to her. But then she handed me a blindfold and told me I’d be walking with it on, so that was pretty wild.”

Caption by Francie Wilhelm.](https://bestofsno.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53535098892_130167352f_o-1200x800.jpg)